I'm from Minnesota, and winter seems like it might happen this year. I guess I was missing it because I'm preparing to reminisce the hell outta this post. About winter. Concerning weather I should be writing elsewise, but I'm a bad person. So this will be but a bullet-point. You fill in the proceedings. (And perhaps I'll hint)...(or did). The pre-proceedings:

I grew up in a log home along a rural portion of the Minnesota river valley. I have memories. I lay them like logs:

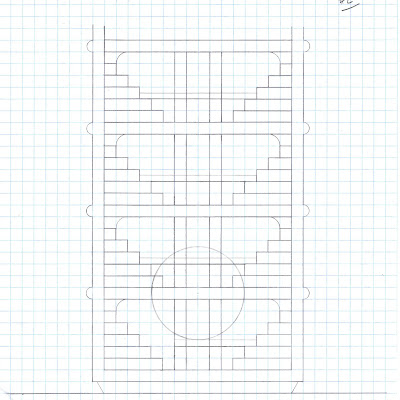

Long Lake here, Horseshoe Lake across it like so. The front door is framed out of a ravine: great wedge cut from flesh of The Earth, spreading down and out from a point behind my house. It begins only with sky and grass but quickly becomes dark and submerged under the arching of trees. I imagine there is an ancient obsidian arrowhead sleeping somewhere in dirt of which one lengthwise and breadthwise half is a miniature negative. Its ridges and grooves a perfectly inverted map. I can feel it here between my fingertips.

|

| A map |

We would follow this ravine's silent, kind belly down to Long Lake, and emerge.

I'm very young as I remember black holes in the white, isolated image of this frozen lake. Next to the holes and the same color are mounds of speared carp, then reaching as high as my head. Their frivolous killers always absent and mysterious - sheer circumstance their prey and everything physical its offal. It looked as though these were piles of dirt made with a shovel and which with a shovel would unmake the holes. But they could never unmake the holes. A winter scavenger perched atop one pile, gorging; a string of viscera connecting beak with claw, pulled tight and torn. Dirty face-feathers. My slow, shy walk - and always listening to the ice. Eventually, my back to the sadistically-exact middle of the frozen water, big brother and his friend relishing my naive fear (once, a bit south of here, my brother driving our four-wheeler with me on the back along the ice of the Minnesota River itself, scaring me by doing donuts too close to the open moving water; once the tires catching on a frozen peninsula of sand while sliding sideways and so the four-wheeler rolling over and spinning toward the open water with us in orbit like gangling moons; frantic thoughts of Jake, the boy who drowned fifty feet away in second grade; a dreary, dilapidated pine bench at our school, built and inscribed in his memory and eventually, revisited at 21 and melancholy, in lichen. My brother was sorry and we went home and were silent and did not drive on the river again). Back against the ice and its contained darkness, afraid. The deep, guttural sound of cracking, grinding. What strange thing am I in this strange world? Periodic muffled gurglings, like you are lain akimbo with eyes closed across your own upset belly. Am I to the world, or am I merely in it? It seems some great thing, I would like for it to see me.

I'm very young as I remember black holes in the white, isolated image of this frozen lake. Next to the holes and the same color are mounds of speared carp, then reaching as high as my head. Their frivolous killers always absent and mysterious - sheer circumstance their prey and everything physical its offal. It looked as though these were piles of dirt made with a shovel and which with a shovel would unmake the holes. But they could never unmake the holes. A winter scavenger perched atop one pile, gorging; a string of viscera connecting beak with claw, pulled tight and torn. Dirty face-feathers. My slow, shy walk - and always listening to the ice. Eventually, my back to the sadistically-exact middle of the frozen water, big brother and his friend relishing my naive fear (once, a bit south of here, my brother driving our four-wheeler with me on the back along the ice of the Minnesota River itself, scaring me by doing donuts too close to the open moving water; once the tires catching on a frozen peninsula of sand while sliding sideways and so the four-wheeler rolling over and spinning toward the open water with us in orbit like gangling moons; frantic thoughts of Jake, the boy who drowned fifty feet away in second grade; a dreary, dilapidated pine bench at our school, built and inscribed in his memory and eventually, revisited at 21 and melancholy, in lichen. My brother was sorry and we went home and were silent and did not drive on the river again). Back against the ice and its contained darkness, afraid. The deep, guttural sound of cracking, grinding. What strange thing am I in this strange world? Periodic muffled gurglings, like you are lain akimbo with eyes closed across your own upset belly. Am I to the world, or am I merely in it? It seems some great thing, I would like for it to see me.

|

| My brain, in section. |

Of its things I love best is when the air is so still that snowflakes fall almost straight, nudged around by only the inertia of individual air molecules themselves which are fixed like pegs into the calm with the snow tumbling down through them like a divine version of games of Plinko seen on lazy summer TV. And if you stay quiet you can hear these collisions, grazings, the collective white noise, like water through a sieve but so much softer. And it is snowing so thickly and the flakes are so big that you can also faintly hear their patter on your eyelashes and shoulders and you can feel an acoustic smothering to the air, like when you were young and would hide under sheets.

Snow is a strange phenomenon as long as you live. It is your finally being granted a pause in the ceaseless turning of the world to be lone, to be a soul in the world, set apart like a jewel. (And I wonder, are cats' whiskers bewildered by a heavy snow? Do they feel the world closing in, invisibly?)

And carving architecture out of the glittering latticework of snowdrifts and my father pushing snow into piles with his old, rusting Ford tractor (my ankle-bone badly burnt across that hot muffler) for us to play in. Learning through experience of spanning, arching, of compressive structures built in gossamer brick. A few heavy collapses and childishly sincere fears of death. Icy rotundas with "skylights" and "shelving" and "beds" and "storage for snowballs" and maybe even multiple rooms for increased resale value. And always destroying them in mercy because they were ours, we were the ones who created them but we must leave. We cannot not stay with you.

UPDATE: No, winter is not going to happen this year.

UPDATE: No, winter is not going to happen this year.